Brushes & Brainwaves

As the instrument that allows us to perceive our fragile human existence, it’s no wonder that the human brain is an incredibly complex black box that we might never understand. It is the seat of our thoughts, emotions, and memories - a complex network of neurons firing in exquisite harmony (more or less!). Yet, at the same time it is also extremely delicate and vulnerable to innumerable neurological diseases and disorders that can rewire who we fundamentally are.

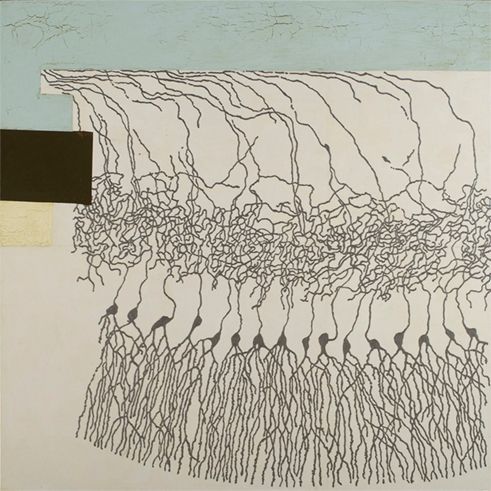

In our last blog post, we looked at what neuroaesthetics is, and the questions it endeavours to answer. Along with studying how observers react to artworks, neuroaesthetics also investigates how artists’ brains might be engaged when creating artworks. The brushstrokes of a painting or the notes of a melody can offer a unique glimpse into an artist’s mind!

In recent years, scientists have found something very intriguing... artists dealing with the after-effects of stroke or suffering from brain damage show altered artistic production in several unique and paradoxical ways, in some cases, even making the art they produce ‘conventionally’ better!

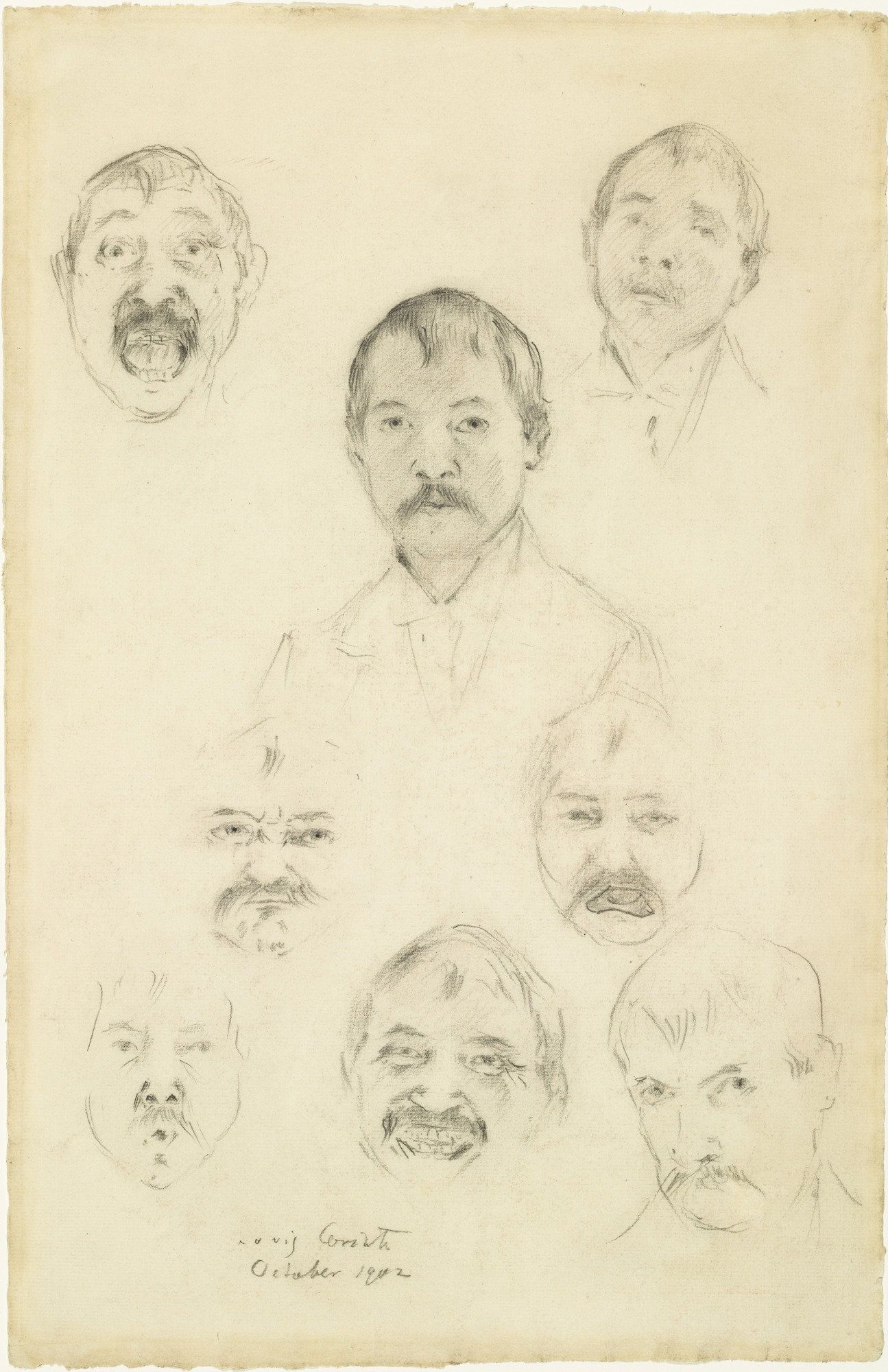

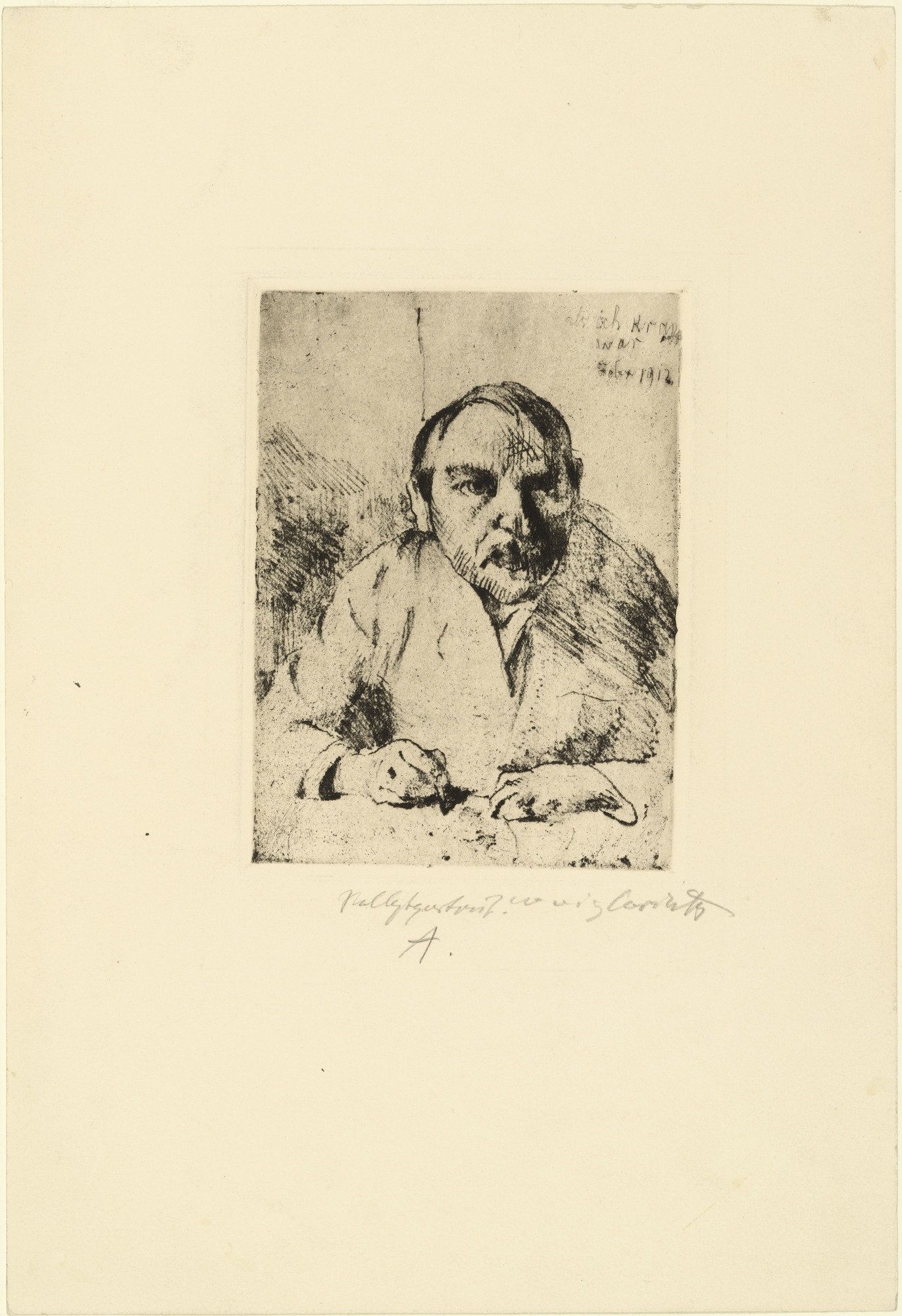

Take the example of Lovis Corinth, a notable German artist who suffered a right hemisphere stroke¹ in 1911, which unfortunately left him partially paralyzed. His stroke affected his ability to include details and textures on the left side of his portraits [1]. Damage to the right hemisphere damage can cause left spatial neglect, leading to artists omitting the left side of their creations. Yet, his brushwork became more vigorous, and the artworks he produced after 1911 are often considered his best work! Loring Hughes, another artist who also experienced a right hemisphere stroke, faced difficulties with spatial relationships between lines. As a result, she had to abandon her previous style of realistic depictions and instead found inspiration in her imagination and emotions [2].

Sometimes, artists who have suffered damage to the brain’s left hemisphere are found to produce artwork that is more vibrant in colour and content. Zlatyu Boyadzhiev, a Bulgarian painter, for instance, used to have a natural and pictorial style, relying mostly on earth tones, but following his stroke in 1951, his paintings became more fluid, energetic, and even fantastical, with richer and brighter colours [3]. Similarly, Katherine Sherwood, an artist from California who also suffered a left hemisphere stroke, used to create "highly cerebral" pieces, featuring esoteric images of cross-dressers, medieval seals, and spy photos. Following her stroke, Sherwood was forced to relearn to paint with her left hand. She adopted a more gestural painting style by working flat and pouring paint directly onto her canvases and her style became "raw" and "intuitive” [4].

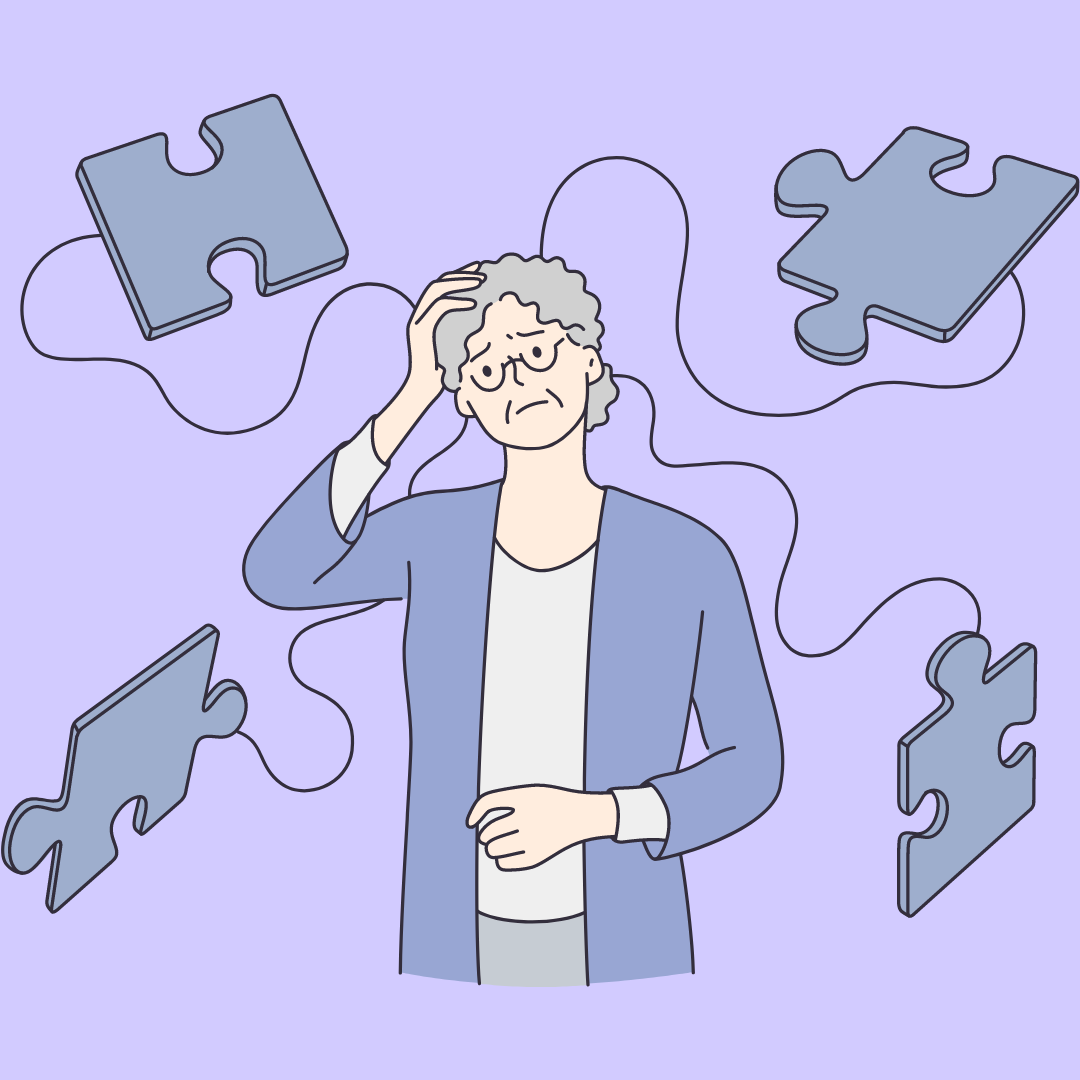

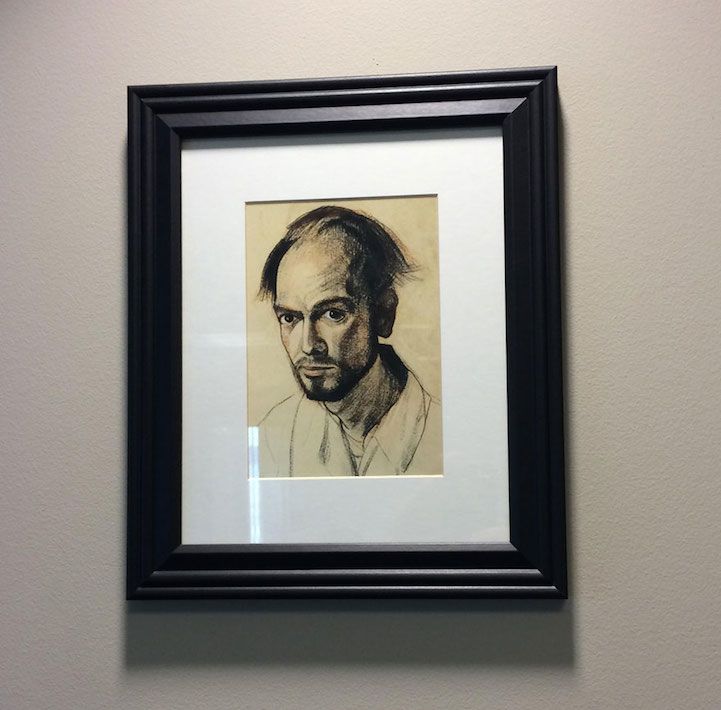

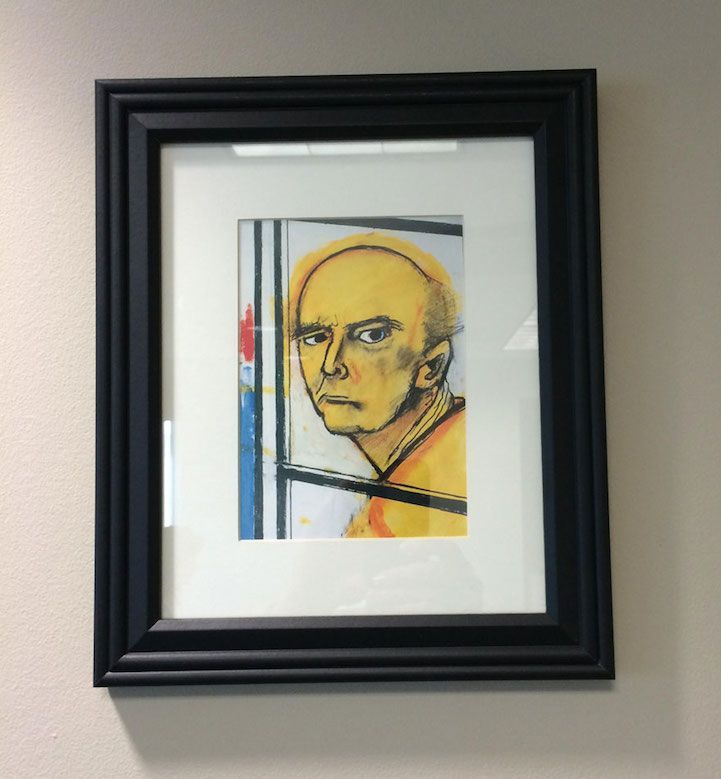

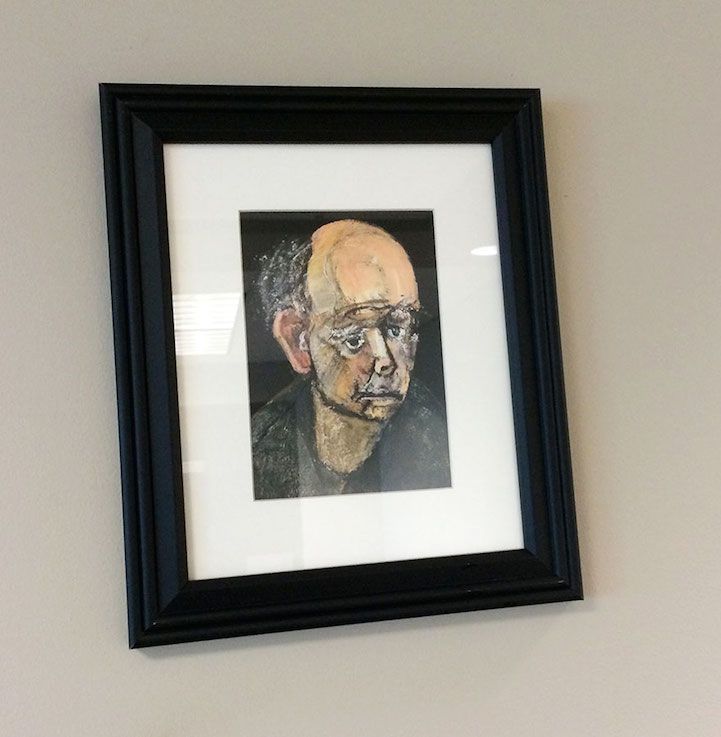

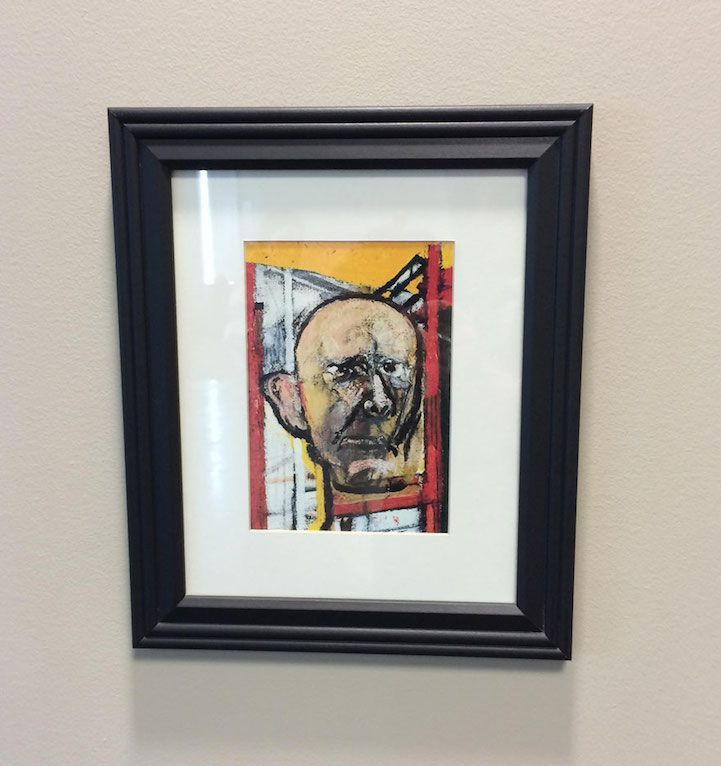

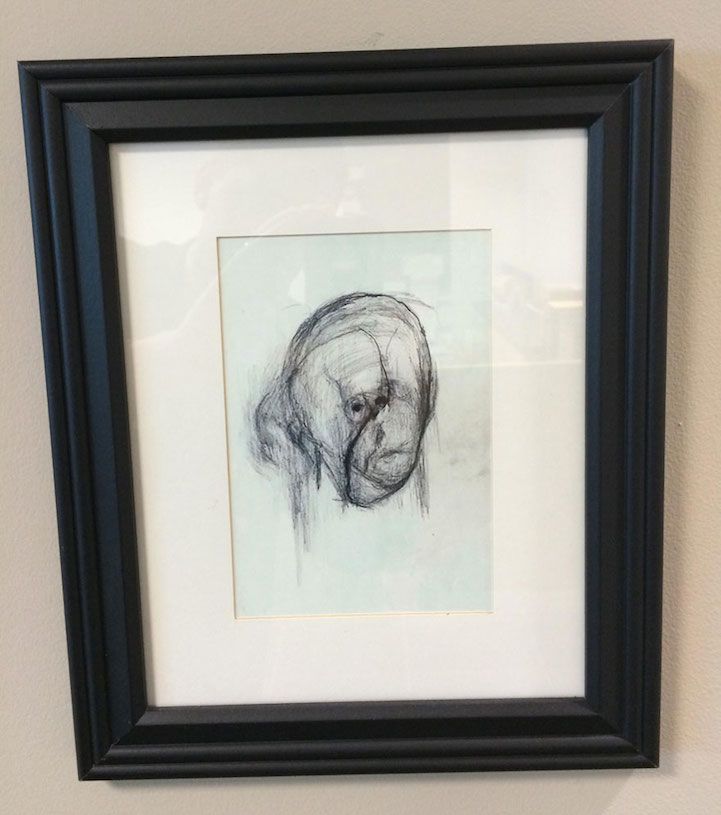

Some artists with Alzheimer's disease have persisted in painting, producing works that reflect their psychological state [5]. William Utermohlen, for example, created several self-portraits that became progressively simpler and more distorted, yet still conveyed his inner world. Another well-known artist, Willem de Kooning, continued to paint even after the onset of Alzheimer's, and some experts argue that this marked a new, coherent style.

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1967

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1996

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1996

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1997

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1997

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1998

Button-

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 1999

Button

Slide title

William Utermohlen Self Portrait 2000

Button

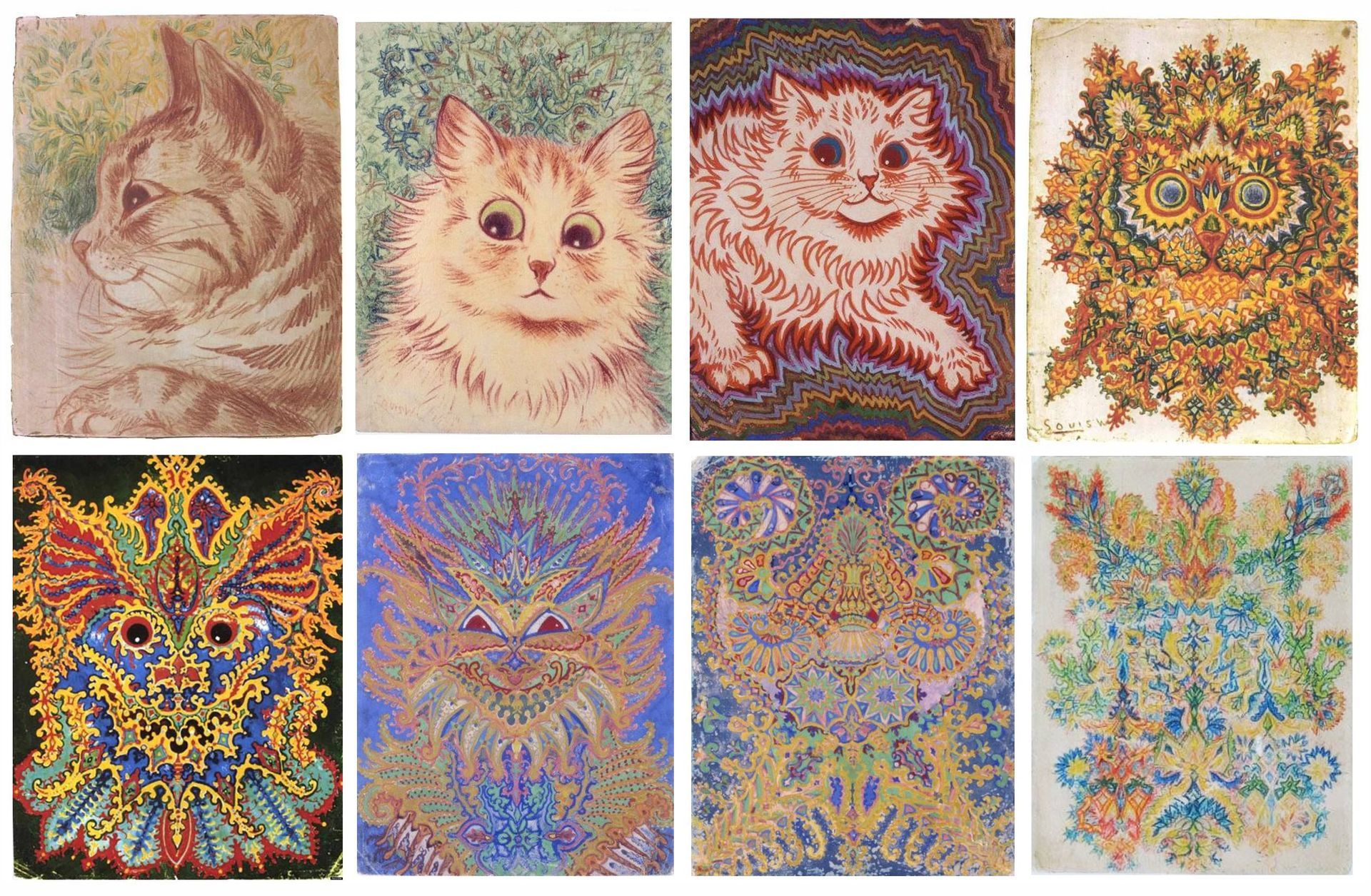

Louis Wain was a British artist born in 1860 who was known for his whimsical and anthropomorphic illustrations of cats in various settings. Over the years, his style progressed from more traditional representations of cats to introducing anthropomorphic elements into his cat illustrations (adding human like facial expressions and clothing), to increasingly abstract and psychedelic interpretations (highly intricate and colourful patterns, with cats often merging into kaleidoscopic designs). Wain's changing style coincided with his deteriorating mental health. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a mental disorder characterized by distorted thinking and perception. Neuroplasticity, the brain's ability to reorganize itself, also plays a role in artistic evolution as both the brain’s structure and functions may be altered in people with schizophrenia (neuroplasticity is in itself a fascinating concept and I hope to cover it in a future blog)!

The fact that art can improve after neurological damage suggests that the brain does not have a single "art module" but instead coordinates different components flexibly across the brain. Brain damage can alter these components, leading to an artistic output that relies on a different set of elements within this ensemble. You might have heard of the left brain-right brain dichotomy; the right brain is often referred to as the creative half, and artistic abilities are thought to rely solely on the right hemisphere. Well, that’s a misconception! In fact, both hemispheres of the brain participate in artistic production and damage to either can lead to changes in the art created by artists.

By no means are we saying you should go get some brain damage to improve your art! But neurological disorders and their impact on art production provide a fascinating insight into the human brain and mind. Indeed, an important question for neuroaesthetics to unravel is whether brain damage leads to changes in art production because regions in the brain are impacted, or because art becomes a personal way for the artist to deal with their injury or trauma. Indeed, art has the remarkable capability to transcend constraints imposed by neurological disorders, acting as a means of expression and communication. Or perhaps we as humans tend to overestimate the value of creations that are produced out of some kind of trauma! All valid empirical questions!

Studying the neural mechanisms of artistic expression offers insight into art's transformative power. Neuroaesthetics provides a glimmer of hope, not only for individuals living with neurological diseases but also for our broader understanding of human experience through art.

- Varun Kheria, Science Communicator, ARISA Foundation

Founder’s note:

I find the paradox of brain damage and beautiful art utterly fascinating. Does brain damage really lead to extraordinary art? Or is it just the perception of the audience that changes once they know the context in which the art was created? Is it the novelty of the art or the actual skill of the artist that impacts its value? How does the brain rewire itself to make new connections that manifest into unique creative productions? There are always more questions than answers, and I am glad I get to ask them day in and day out! :)

References:

- The Shattered Mind

- Cognitive and Emotional Organization of the Brain

- Mind, Brain, and Consciousness: The Neuropsychology of Cognition

- How a Cerebral Haemorrhage Altered my Art

- Changes in painting styles of two artists with Alzheimer's disease

- Cover Art: Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Götz von Berlichingen (1917), Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund.

Footnotes:

¹ A stroke is what happens when blood supply to part of the brain gets blocked or when a blood vessel in the brain bursts. In either case, the part of the brain where this occurs becomes damaged or dies.