The Canvas of Perception

Neuroscience is a subject that has always fascinated me, but I never imagined that I would actively get involved with it. It always seemed too intimidating and intense, and honestly, it wasn’t my first choice. While I loved every aspect of science a lot, for as long as I can remember, I had my heart set on becoming an astrophysicist and following in Carl Sagan’s footsteps. I was well on my way to doing so too, by studying astrophysics at Boston University, but a host of extraordinary situations forced me to drop this course and move back to India.

I still loved science immensely and wanted to become a science communicator. Eventually, I came across ARISA Foundation. Its focus on the intersection of arts and sciences while encouraging academic research was something I felt India’s academia needed more of. I found something I thought I’d never be a part of in this lifetime – an interdisciplinary approach to psychology, art, and neuroscience. The blog and my work as ARISA’s science communicator is an outlet for me to express my deep love and reverence for all things art and science.

So how do art and science come together at ARISA? One of the many ways in which ARISA bridges science and art is through research in the field of Neuroaesthetics.

What is Neuroaesthetics?

Have you ever wondered why certain artworks, music, or landscapes evoke intense emotions within you? Do you ever find yourself mesmerized by both the elegant contours of a sculpture and the hues of a particularly beautiful sunset? Why do these experiences move us? If these questions resonate with you, you might find the field of neuroaesthetics worth exploring. Neuroaesthetics is a relatively new discipline in the field of cognitive neuroscience, and is the ‘scientific study of the neural bases for the contemplation and creation of a work of art’ [1]. As a field, it attempts to unravel the complexities behind our aesthetic experiences by examining the intricate mechanisms of the brain. In this blog post, we will delve into what neuroaesthetics is and how our brain might go about perceiving art.

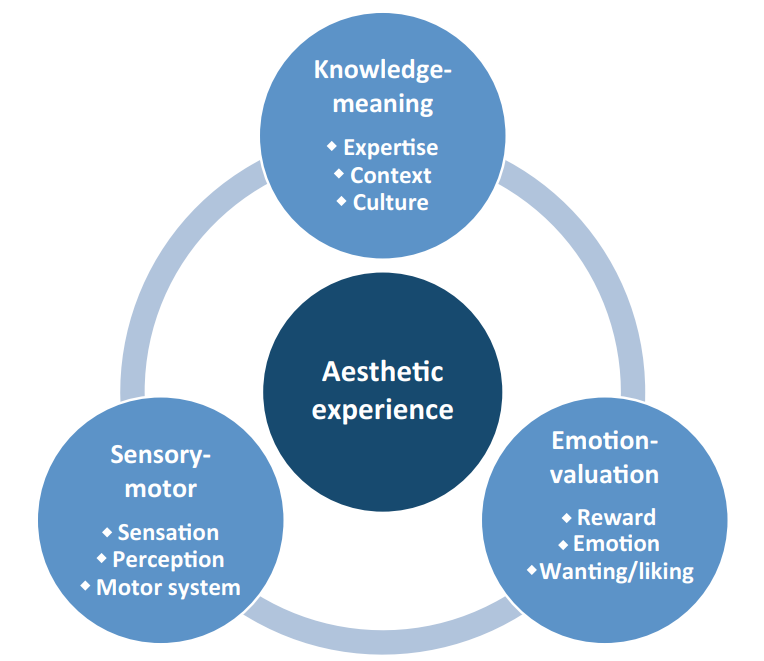

The Aesthetic Triad

The Aesthetic Triad is a model put forth by leading researchers in the field of neuroaesthetics – Dr. Anjan Chatterjee and Dr. Oshin Vartanian [2]. The triad model explains how the brain might work when engaging in an aesthetic experience. It can be broken down into the following neural systems: sensory-motor, emotion-valuation, and knowledge-meaning. But what does this mean? Earlier studies of aesthetic experiences have proposed that different aspects of an object are analysed by our brain in distinct information-processing stages. Researchers have tried to identify and map the neural structures in our brain responsible for processing these distinct stages.

Understanding The Aesthetic Triad Model

Our visual brain processes information in a complex way. It can distinguish between different aspects such as colour, brightness, and motion, as well as more complex structures such as faces, bodies, and landscapes. These sensory systems are actively involved in aesthetic experiences. For example, when we observe Van Gogh's dynamic paintings, we perceive a subjective sense of motion and stimulate the ‘visual motion areas’ known as MT+. Conversely, portraits activate the ‘face area’ in the fusiform gyrus (FFA), and landscape paintings activate the ‘place area’ in the parahippocampal gyrus (PPA) in the brain. One might wonder, could these sensory areas play a part in evaluating these visual elements as well, rather than simply identifying them? Would the motion areas also be stimulated when looking at Warli paintings which often include dynamic spiral structures? Neuroaesthetics explores such questions and more!

When viewing paintings that depict actions, specific regions of our brain's motor system are activated, which is linked to something called The Extended Mirror Neuron System. Mirror neurons respond to both the execution and perception of actions and were initially found in monkeys. Harken back to the phrase: monkey see, monkey do. A similar system can be found in humans [3]. What that means is the system in your brain that is activated when you do an action is also activated when you just view that action! We’re essentially mirroring each other’s actions quite often. 🙂

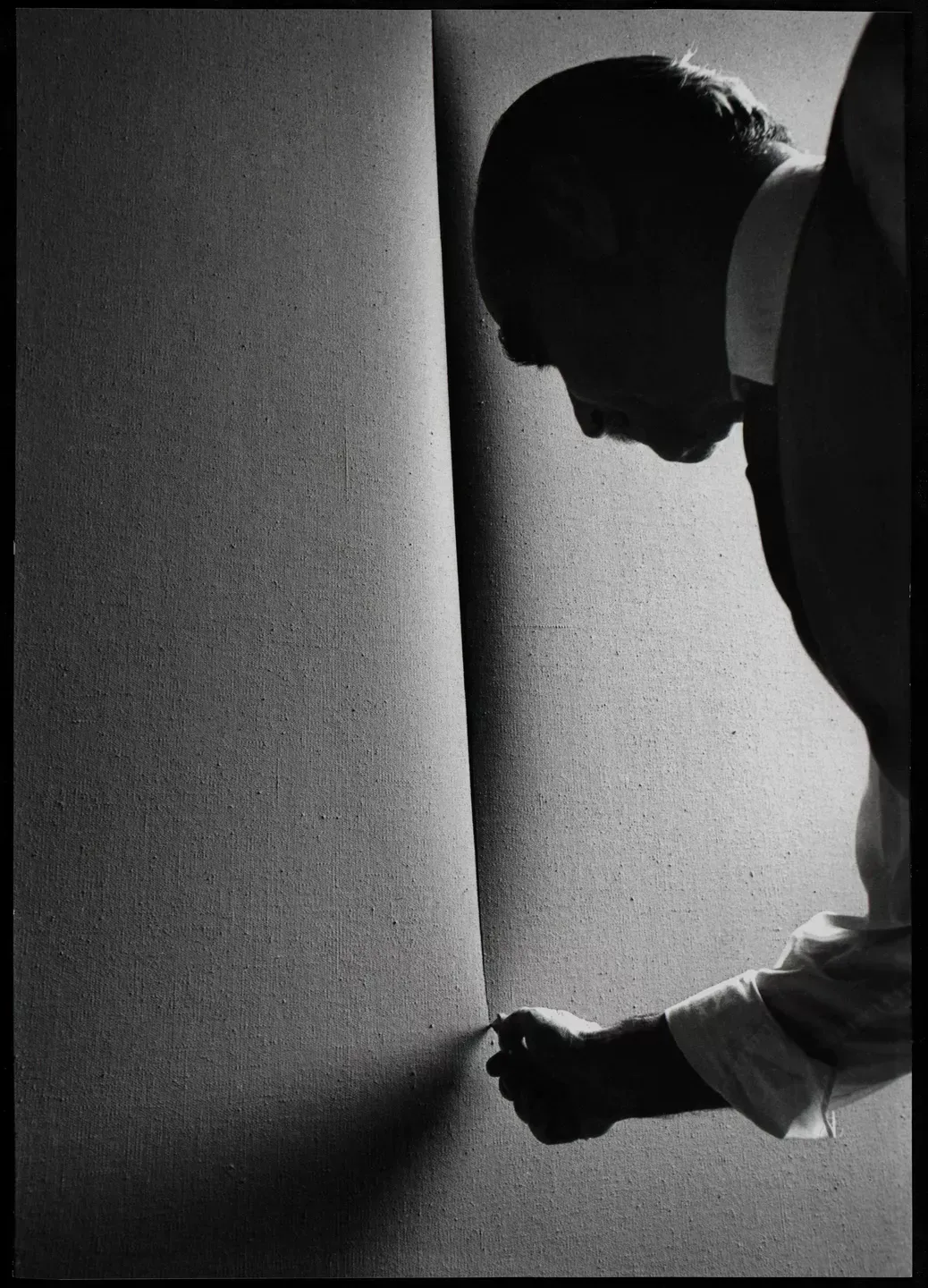

And in the context of neuroaesthetics, the mirror neuron system may be activated when interpreting the purpose of artistic gestures or observing the outcomes of actions. One example of this could include Lucio Fontana's cut canvases – researchers propose that even just observing the visible traces of an artist’s movement like the cuts on canvas can activate relevant sensory-motor areas in the viewer’s brain (without actually viewing the cutting action itself)! Cool, right?

So that’s the sensory-motor part of the triad. What about emotion-valuation?

Looking at aesthetically pleasing objects can elicit a sense of pleasure within us. For example, when viewing attractive faces (think of your crush!), even if we are not consciously thinking about their attractiveness, the ‘reward network’ might get engaged. The reward network responds to other sources of pleasure too – such as music you like or architectural spaces you find pleasing. This reward system consists of ventral and orbitofrontal neurons (among other regions) and is engaged for any kind of rewarding stimuli we perceive around us, not necessarily artworks. Neuroaesthetics can also explore whether there is a kind of “common currency” that drives preferences across art and non-art domains!

What makes up the knowledge-meaning component? For me, this is the most interesting one! The context in which art is encountered also changes how we perceive aesthetic experiences. Research has revealed that individuals tend to be more drawn to abstract 'art-like' images if they are labelled as being from a museum, as opposed to being computer-generated [4]. The preference for art said to be from a museum was linked to increased neural activity in the reward network. Similarly, knowing whether artworks were original or forgeries changed aesthetic preferences [5] – people liked originals more than forgeries; no surprises there, right? People's judgments are influenced by their belief systems, and past memories and experiences, which can positively or negatively impact their visual enjoyment. This part of the triad explains why even when viewing the same painting, people might have different responses – the context in which they see the painting, and their own backgrounds and experiences influence their experience.

So how do these three systems work together? When evaluating any art, our brain combines the sensory inputs it receives with our affective responses and emotions, and contextualises them within our past experiences, surroundings, and culture to create a unique aesthetic experience for all of us. We all have the aesthetic triad in our brains really – art is universal because it arises from the same neural systems in all of us [6]. But it is also individual and variable because these systems are flexible in that they develop through a lifetime of experiences and are engaged differently depending on how they attune to individual contexts and goals. What a strangely beautiful paradox!

Neuroaesthetics is more than just comprehending what makes art beautiful. It is a field that aims to unravel the mysteries of the human mind and explore the profound connections between aesthetics, emotion, and cognition. By studying the neural basis of our aesthetic experiences, we can gain a deeper appreciation of our humanity and unlock new possibilities in art, design, therapy, and beyond. As we delve further into the beauty of the brain, we may discover that the pursuit of aesthetics is not just a quest for pleasure but a journey that leads to a richer understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

- Varun Kheria, Science Communicator, ARISA Foundation

Founder’s note:

I first held the human brain in my hand at a brain anatomy lab during my Masters in 2014. It’s been 9 years to the day but I still remember it as if it was yesterday. How can something so small and fragile contemplate its own consciousness? What really is the brain? What is the human mind? How is this small jiggly-wiggly piece of tissue able to have a profound transcendental experience such as the one I have when viewing a painting, reading poetry, or watching and performing dance? In my journey to understand the human brain and mind, I am left with more questions than answers. And my hope is that with Aesthetic Alchemy, I can share some of these questions with you too! 🙂

References:

- Definition of Neuroaesthetics

- The Aesthetic Triad

- The Extended Mirror Neuron System in Humans

- Modulation of Aesthetic Value by Semantic Context

- Assignment of Authenticity When Viewing Works of Art

- Art is Universal