Winter Blues

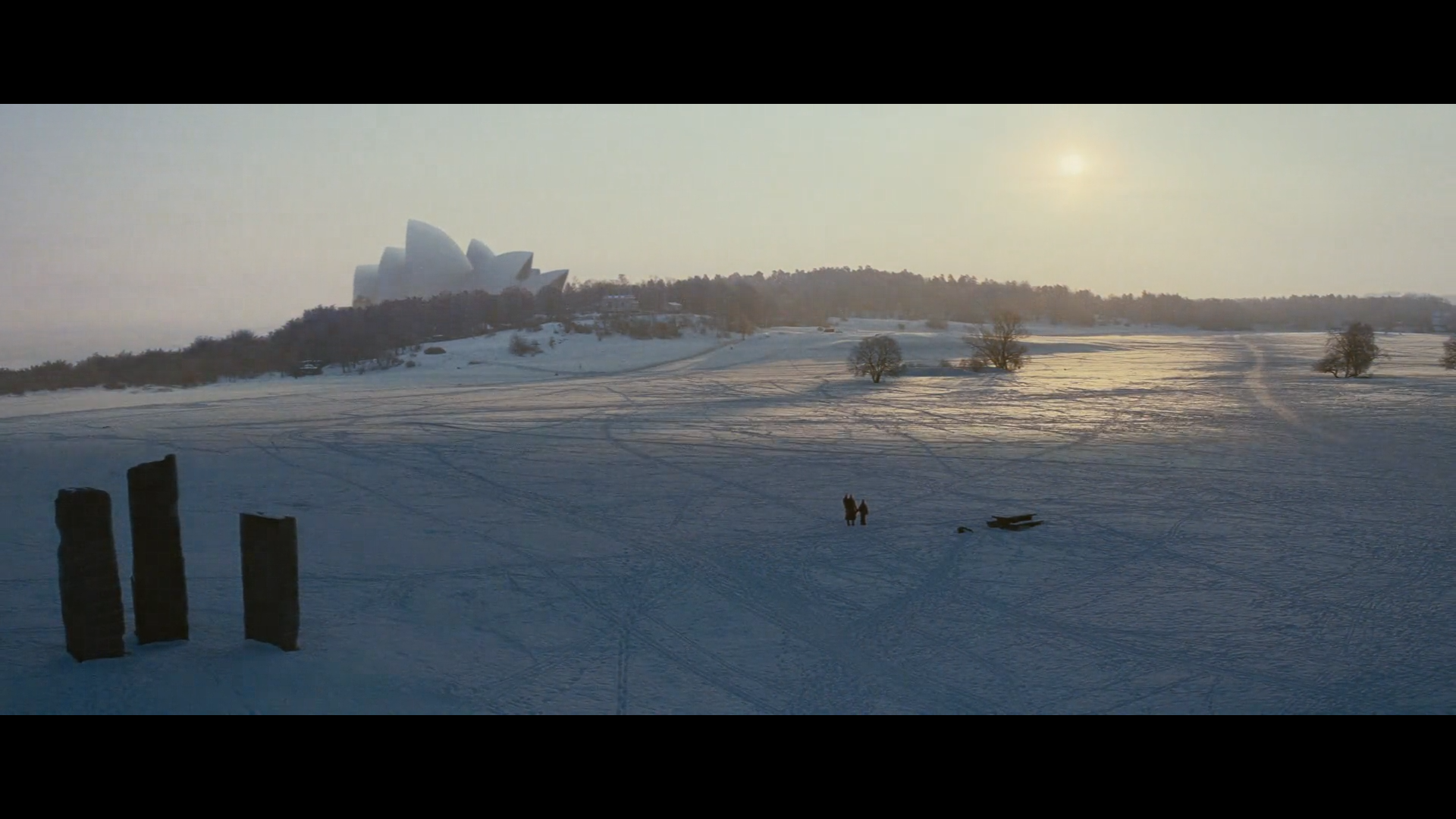

What if I told you that the changing seasons affect your mood? As autumn, the season which has long been associated with love, romance, and joy, is replaced by the coldness of winter, our mood too changes, and not necessarily for the better. The first time I heard that winter could push people into depression, I didn't believe it. After all, the seasons are consistently shifting, and they do it every year. How could this affect someone so strongly? It isn’t as if winter is going to catch us off guard, we know roughly when it’ll show up and what it will bring with it. And yet, a lot of people end up catching the winter blues each year.

Neurological Underpinnings of Seasonal Affective Disorder

As winter approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, the amount and the quality of light we receive during the day changes. The ebb and flow of sunlight has a significant impact on regulating our internal biological clocks, which affects our mood, sleep-wake cycles, and overall well-being. During the winter months, when the days are shorter and the sun's radiance diminishes, some people may experience what they call winter blues, scientifically known as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) [1]. You read that right, the scientific term for seasonal depression is SAD, and whenever I think about this it makes me less so.

People with SAD struggle to balance their mood. A protein called serotonin transporter (SERT) aids in the transportation of the neurotransmitter called serotonin, which regulates mood. Higher SERT levels lower serotonin activity, which can lead to depression [2]. Sunlight lowers SERT levels naturally during the summer, increasing serotonin activity and improving mood. However, as sunlight diminishes in autumn and winter, SERT activity increases, leading to higher levels of SAD. According to a study, individuals with SAD possess 5% more SERT. [2]

SAD is also correlated to the overproduction of melatonin [3]. Melatonin is a hormone that is synthesized by the pineal gland and responds to darkness by making us sleepy. As the days get shorter in the winter, the production of melatonin increases, causing those with SAD to feel sluggish and fatigued by the evening. While it is likely that melatonin plays a role in exacerbating the symptoms of SAD, it is not solely responsible for it.

The increase in SERT and melatonin impacts our circadian rhythms, which is our body’s internal 24-hour clock. The internal clocks of those who have SAD fail to account for the change in the length of the day, making it harder for them to adjust and causing a build-up of stress in their bodies [3].

How can you deal with SAD?

There have been several studies on light and how it can cause SAD since it was first discovered in 1984. Since a lack of sunlight seems to be what causes SAD, and we can’t really ask the sun to shine just a bit brighter during winter days, the solution seems simple enough. The use of bright artificial light that mimic a few qualities of sunlight, especially in the morning, has proven to be effective. This treatment is known as Light Therapy, Bright Light Therapy, or phototherapy [4].

Light boxes that emit full-spectrum light similar to sunlight can be purchased. These boxes can help alleviate symptoms of SAD when used first thing in the morning from early fall until spring. In Scandinavian countries, light rooms are available where light is evenly distributed and indirect [5]. Typically, light boxes filter out ultraviolet rays and require daily exposure of 20-60 minutes to cool-white, fluorescent light during fall and winter which is about twenty times greater than ordinary indoor lighting.

Although we can’t always afford lightboxes. Thankfully, they aren’t the only solution. Well, perhaps the interplay of light and colour that painters conjure up on their canvases could help us. Art can increase levels of dopamine in the brain, which can improve mood and increase feelings of pleasure [8]. The same fluctuations in levels of light which cause SAD can inspire artists to create magnificent paintings that can, in turn help people deal with SAD. Isn’t that kind of poetic?

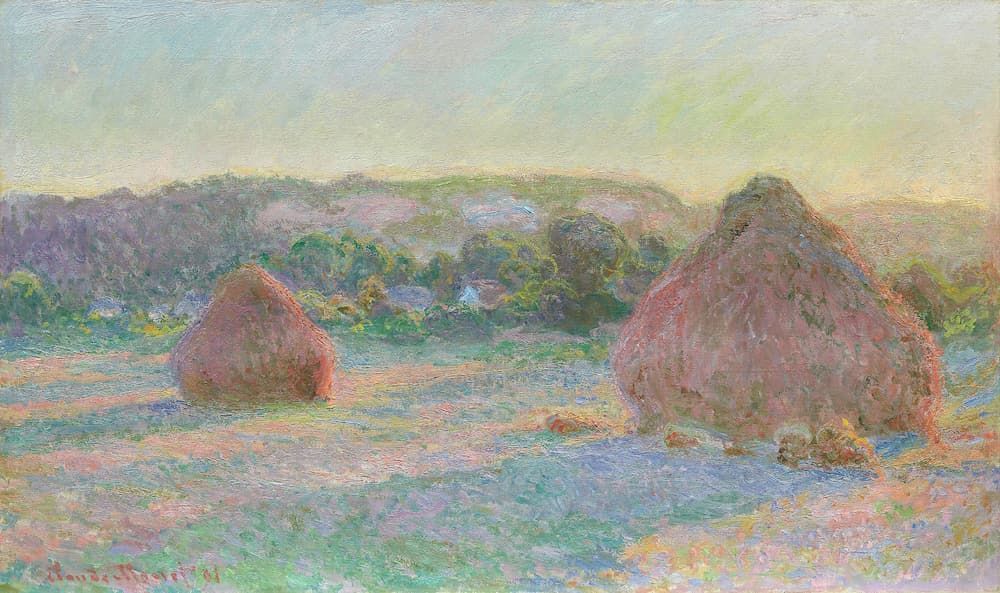

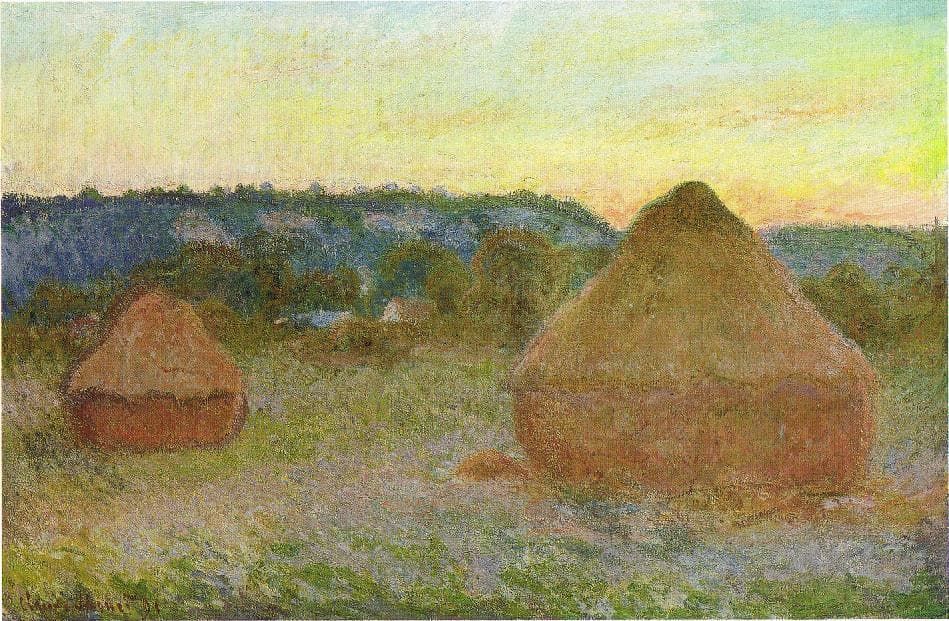

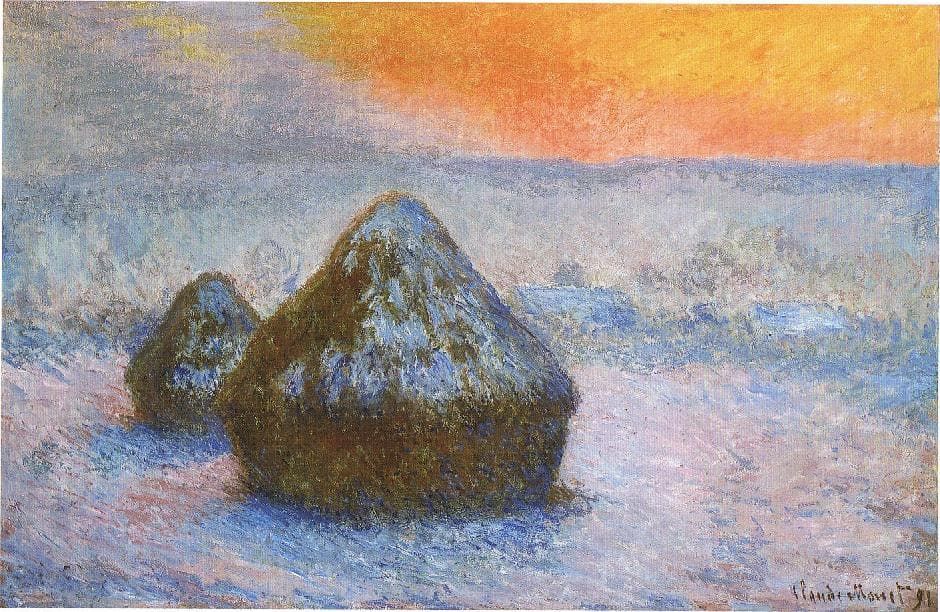

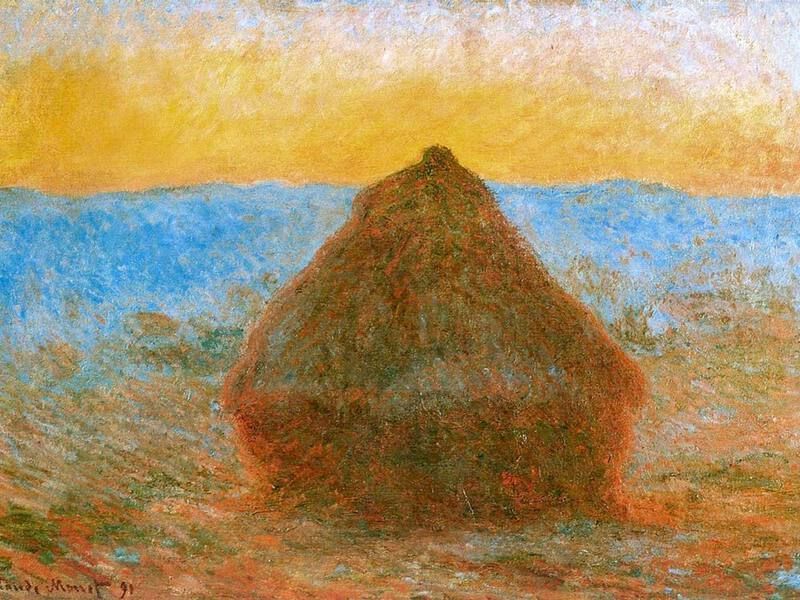

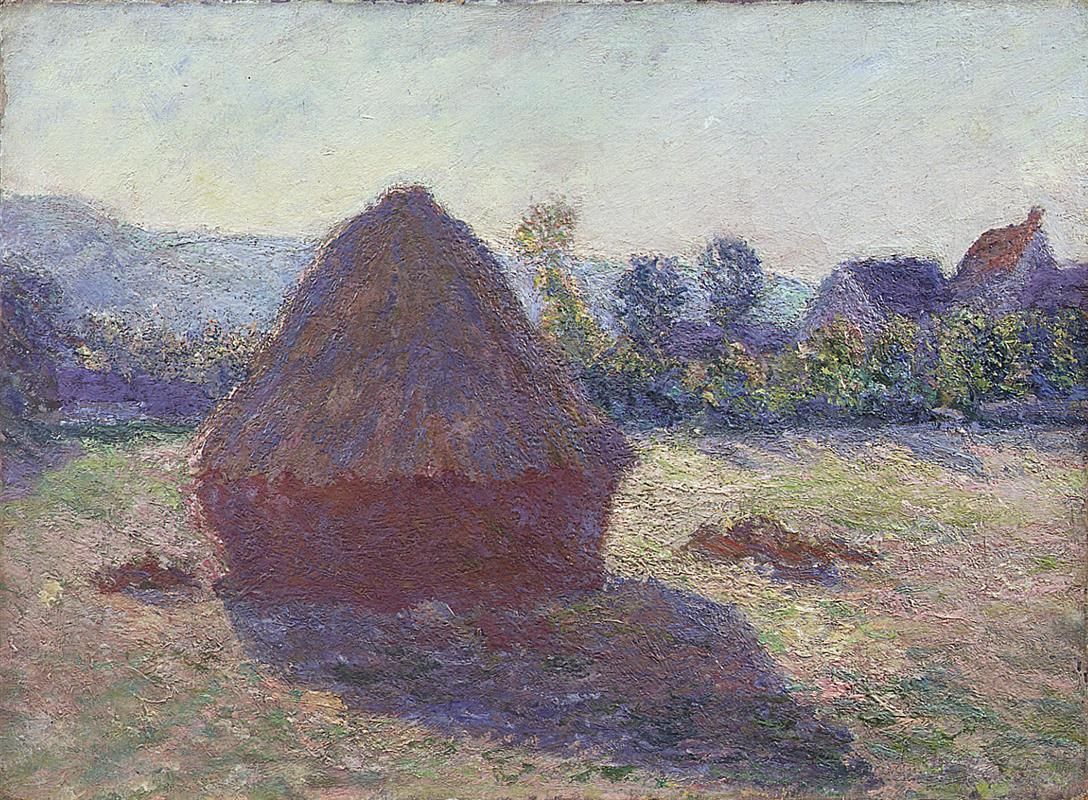

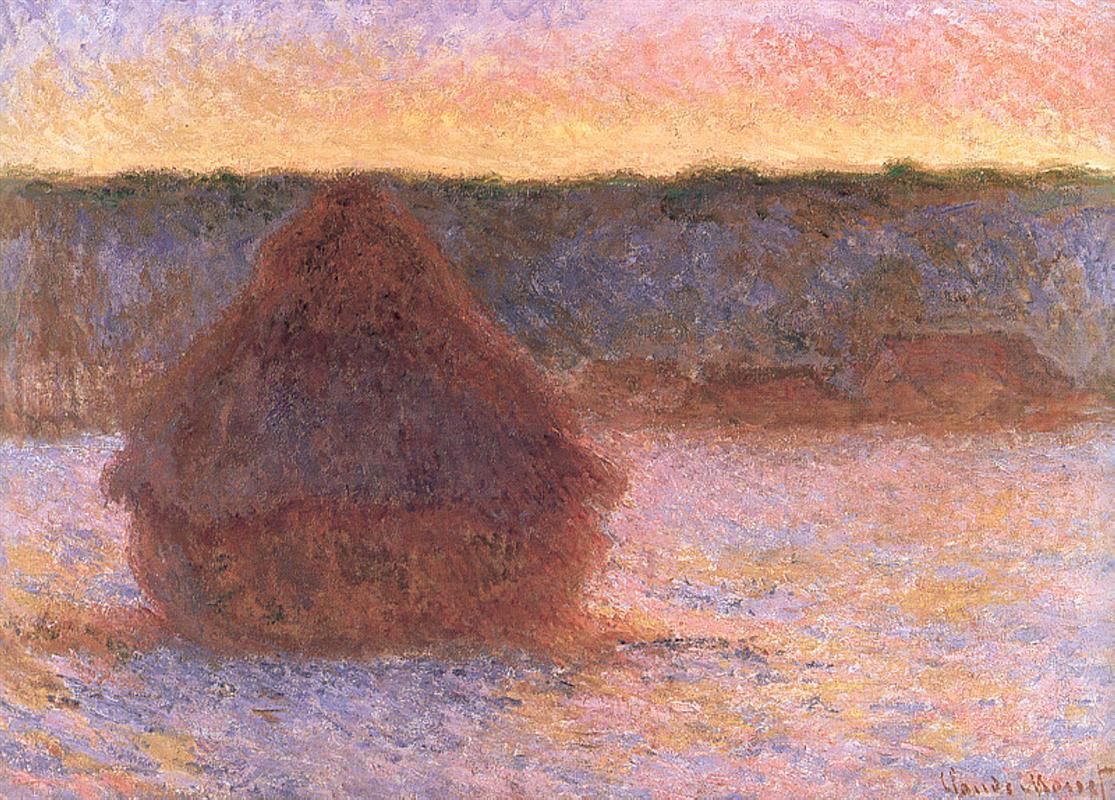

One of my favourite artists is the famous French painter, Claude Monet, also known as the founder of Impressionism. Monet was obsessed with light and how the human mind comprehended colour. Unlike his contemporaries who used to blend colours and use fine line work, he used shorter brush strokes that left solid and distinct colours on the canvas. Similar to the Gestalt school of psychology with their principles of perception, Monet understood that the human mind looks at colours not as individual strokes, but as a collective relationship of colours.

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

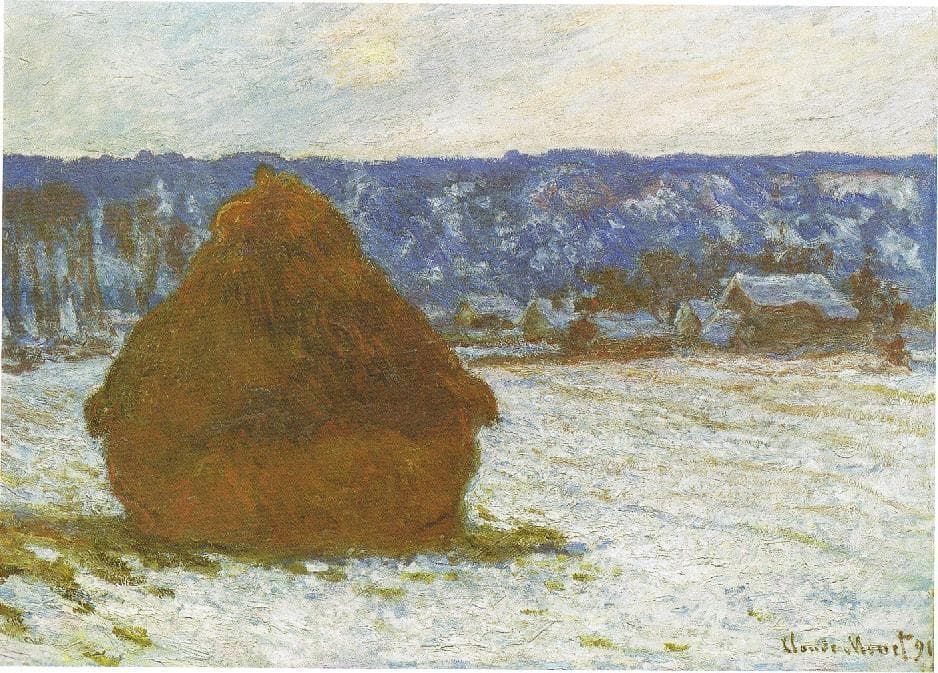

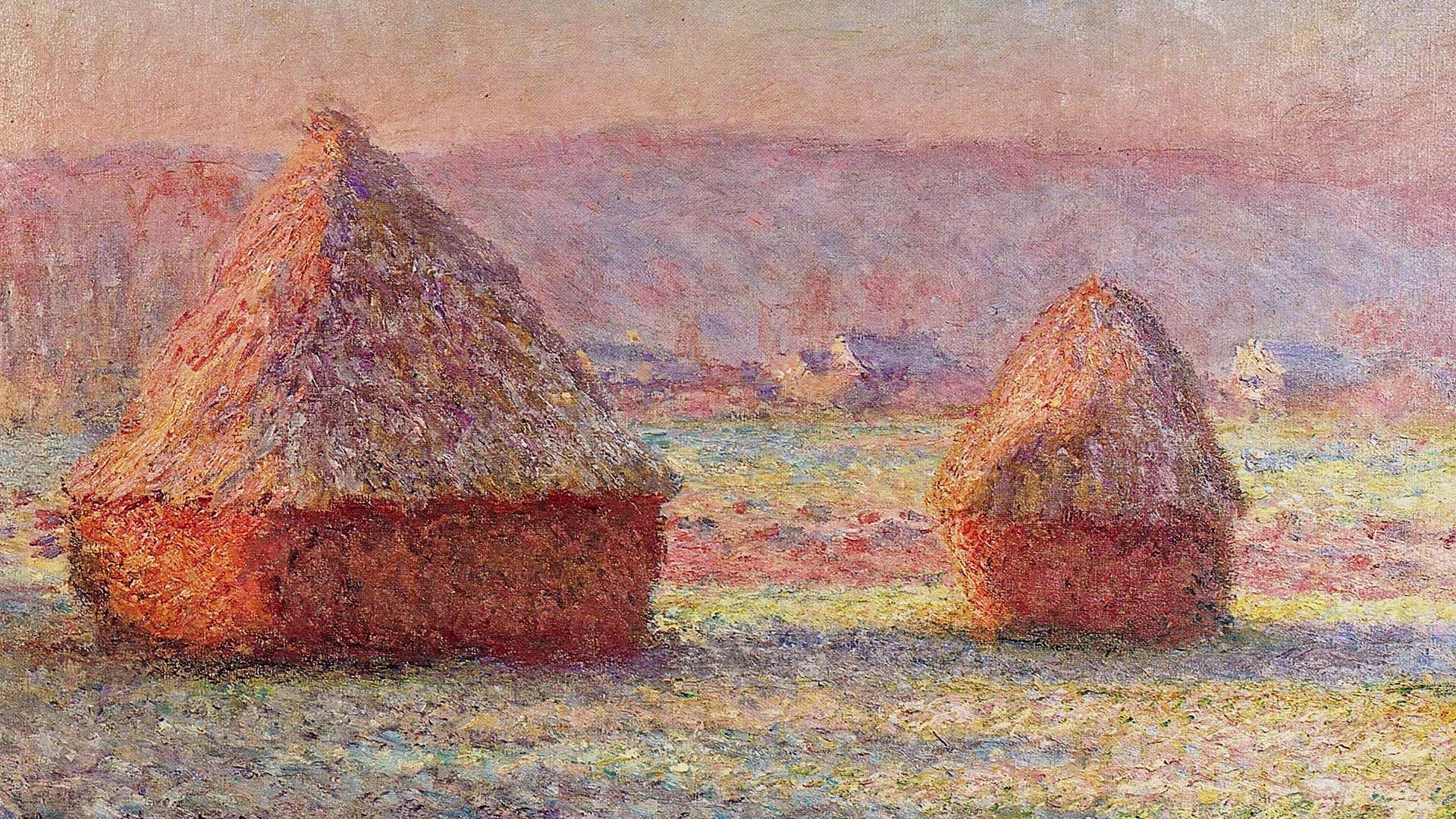

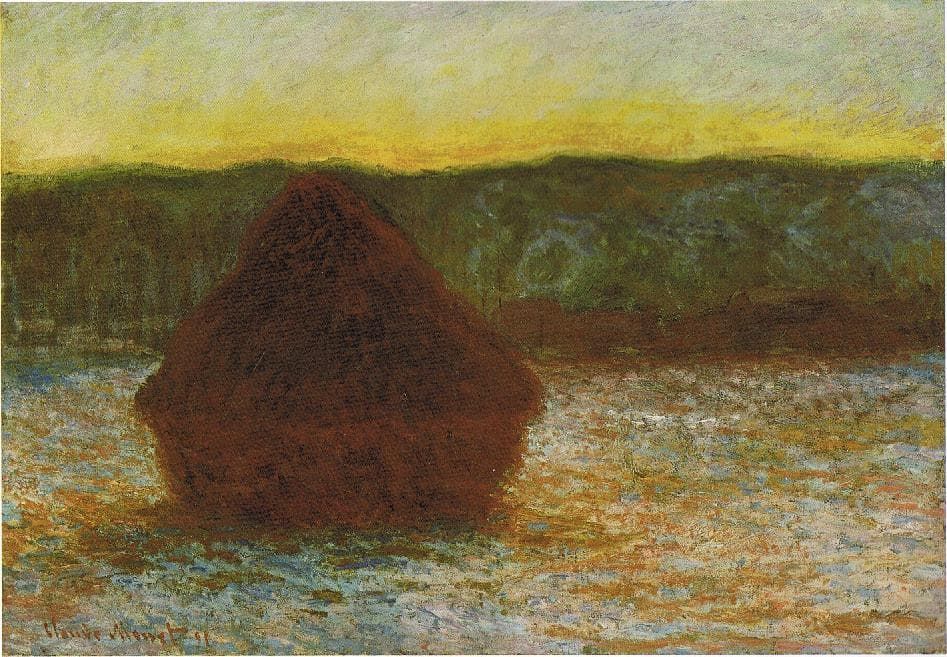

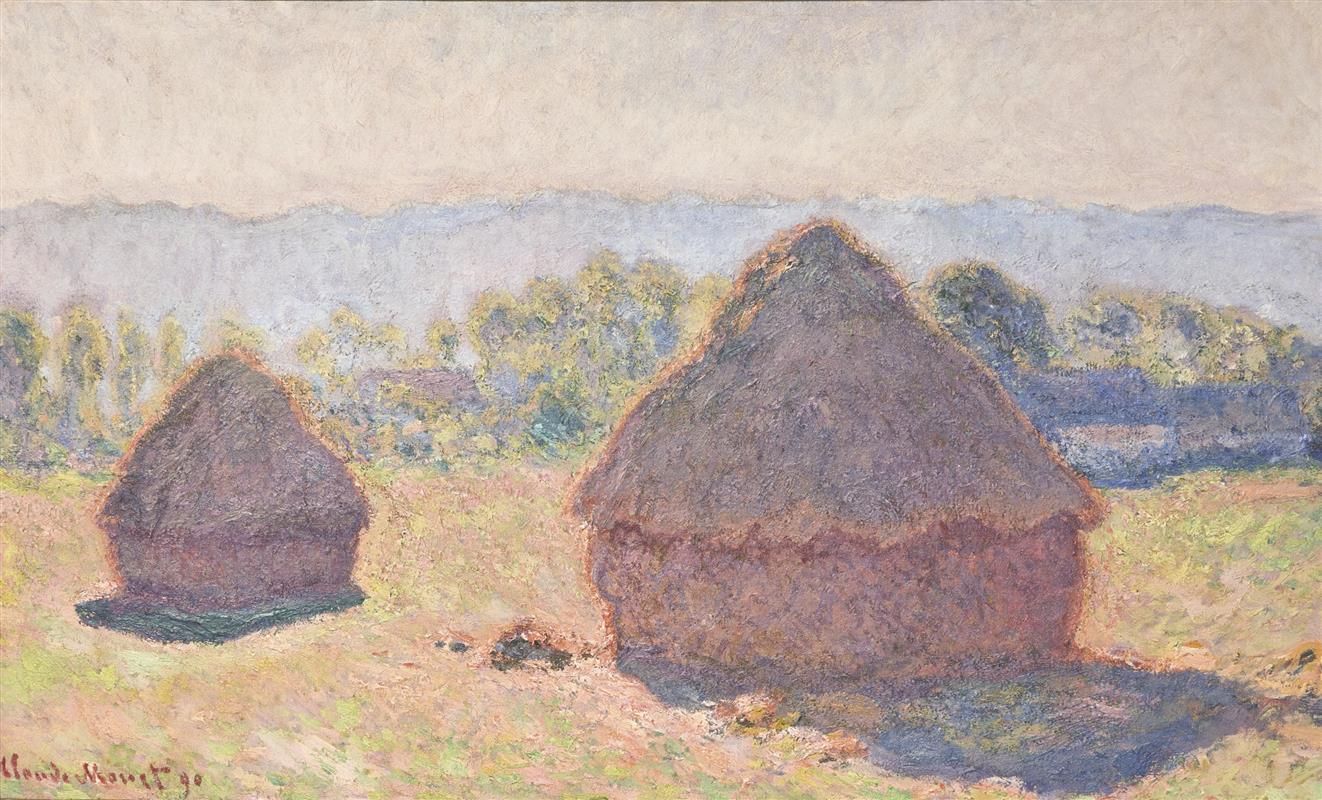

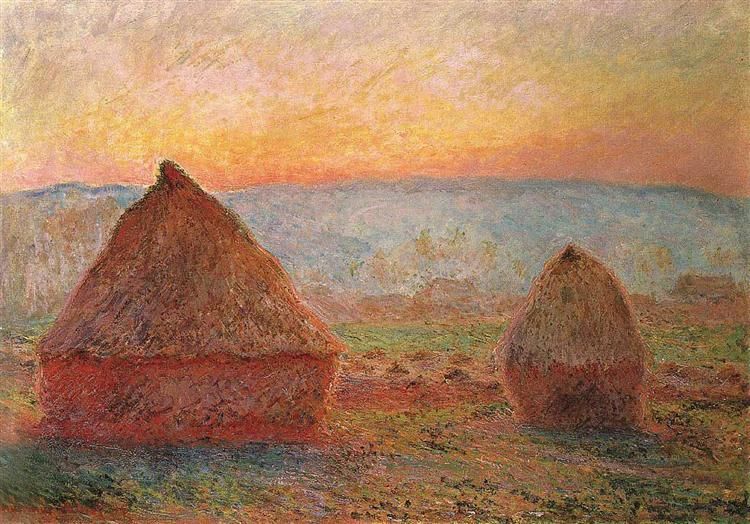

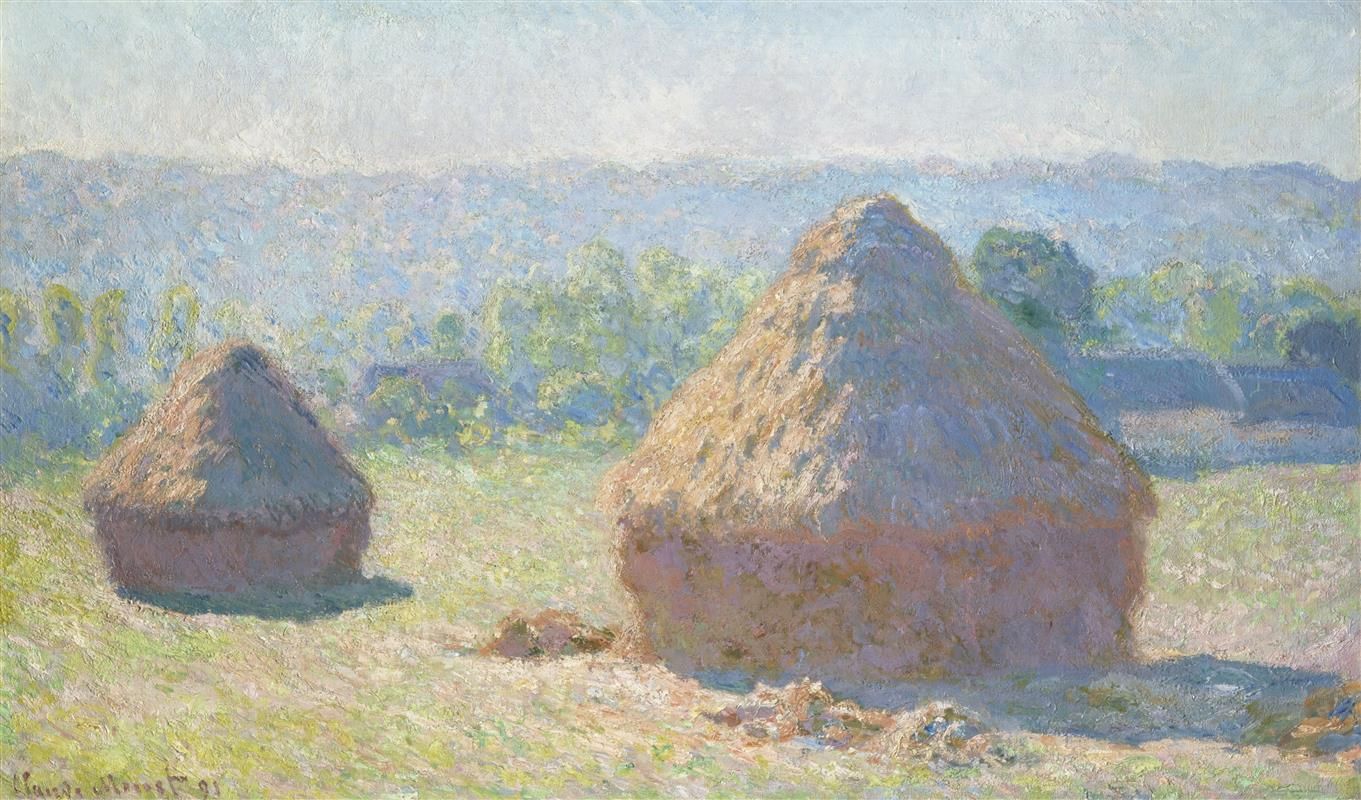

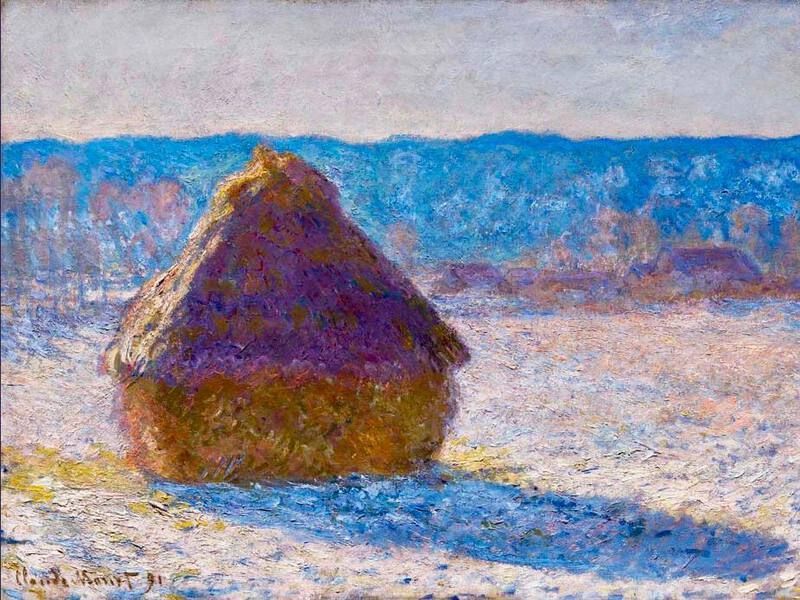

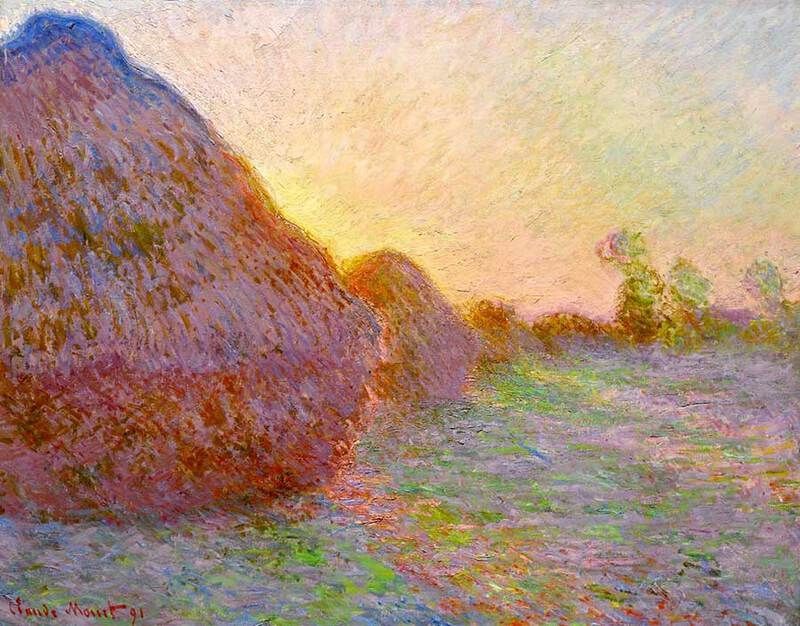

Impressionists like Monet preferred to paint outdoors, or ‘‘en plein air’, instead of in a studio. Working quickly in front of their subjects allowed them to capture the fleeting effects of sunlight and gain a better understanding of light, colour, and the natural scene's shifting patterns [6]. This approach resulted in a greater awareness of the interplay between light and colour and their effects on the natural world. Monet's series of Haystacks, painted between 1890 and 1891, showcases his mastery in capturing the nuances of light. By painting the same subject under various lightings and atmospheres across different times, days, seasons, and weather, Monet was able to capture the ephemeral nature of light. [7]

Light regulates our internal rhythms, evokes emotions, and inspires artistic endeavours, transcending boundaries of the visual spectrum. There is so much we don't appreciate about the beauty of our environment and how something as regular as sunlight has a deeper influence on our well-being. Monet’s Haystacks remind me that the world around us is always changing, but the change can be so gradual that neither our bodies nor minds realize it. Embracing these subtle changes and their impact on us mindfully empowers us to actively nurture our well-being.

- Varun Kheria, Science Communicator, ARISA Foundation

References:

- Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches

- Patients with seasonal affective disorder show seasonal fluctuations in their cerebral serotonin transporter binding

- The circadian basis of winter depression

- Bright Light Therapy: Seasonal Affective Disorder and Beyond

- Improvement in Fatigue, Sleepiness, and Health-Related Quality of Life with Bright Light Treatment in Persons with Seasonal Affective Disorder and Subsyndromal SAD

- IMPRESSIONISM

- Haystacks, by Claude Monet

- Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion