Skin Deep

Beauty holds a lot of power in our world. Its aesthetic appeal captivates us, draws us in, and often leaves us in awe. However, there is a deeper aspect to beauty that goes beyond its physical appearance. It is the subconscious association we make between beauty and goodness. Throughout history, humans have been entranced by the concept of beauty. From the intricately sculpted statues of ancient Greece to the timeless masterpieces of Renaissance art, beauty has been revered, sought after, and celebrated.

Let’s talk about the phenomenon of beauty. When we see beautiful people, certain parts of our brains become activated. Attractive faces activate the fusiform gyrus, an area in the back of our brain that specializes in processing faces, as well as the lateral occipital complex, an adjacent area that specializes in processing objects. Additionally, attractive faces activate our reward and pleasure centers. Our visual brain that processes faces interacts with our pleasure centers, also entrenching our experience of beauty within our prior belief and knowledge systems. [1]

What is it about beauty that compels us to equate it with goodness? Our brains have a stereotype that associates beauty with goodness. This stereotype is deeply embedded within the orbitofrontal cortex, and it triggers neural activity in response to both beauty and goodness. Interestingly, this association occurs automatically, even when people are not consciously thinking about beauty or goodness. This trigger for the association between beauty and goodness may be responsible for the many social effects that arise from this perception. [2] In a 2006 study [2], it was found that ‘unattractive’ women are often at a disadvantage compared to those who are considered average or attractive. It is more common for unattractiveness to be viewed negatively than for beauty to be viewed positively.

Furthermore, as social beings, we are hardwired to look for positive qualities in other people, and physical attractiveness frequently acts as a visual indicator of these traits. From an evolutionary standpoint, we are naturally attracted to features like symmetry, healthy skin, and other indications of good health and fertility, which are typically linked to physical beauty. As a result, our minds have learned to perceive beauty as a symbol of genetic fitness and overall well-being. [3]

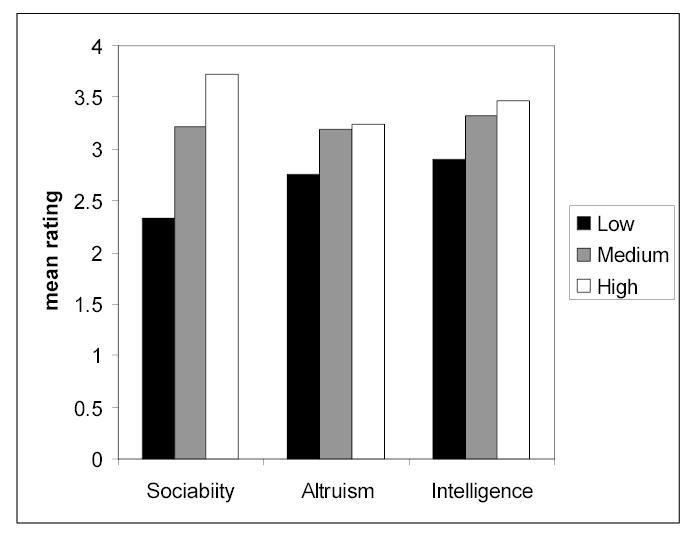

Attractive people receive all kinds of advantages in life. They're regarded as more intelligent, more trustworthy, they're given higher pay and lesser punishments, even when such judgments are not warranted. Research indicates that individuals often attribute positive attributes, such as kindness, intelligence, and trustworthiness, to those they perceive as physically attractive. This phenomenon, known as the halo effect in psychology, results in the unconscious assumption that attractive people possess additional desirable traits. [4]

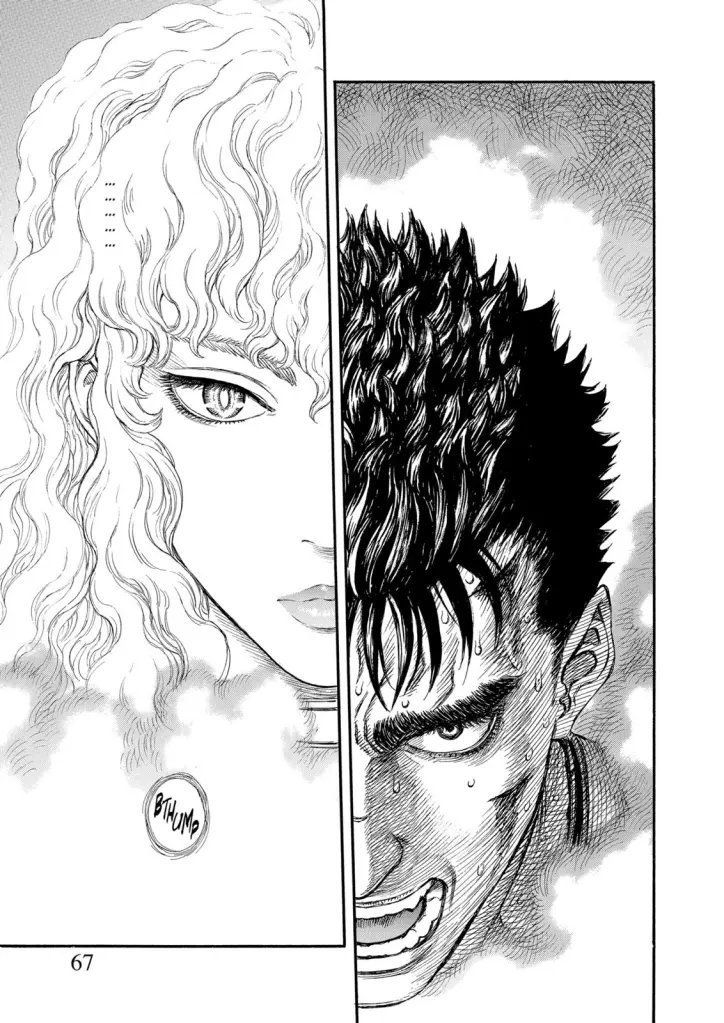

Even in fiction, beauty has been idealized and romanticized in literature, art, and popular culture. Heroes and heroines in myths and legends are often depicted as being exceptionally beautiful, while villains are portrayed as “ugly” or having facial anomalies. These narratives subtly reinforce the idea that beauty is inherently linked to moral virtue - a notion that permeates our collective consciousness.

In reality, however, one need only look at history to see the consequences of valuing external beauty above all else. The connection between beauty and goodness is not always positive. Societies throughout the ages have set impossible beauty standards, leading to discrimination, inequality, and even violence against those who do not conform. Focusing on physical beauty can also overshadow inner qualities such as kindness, empathy, and integrity. When we prioritize outward appearance over character, we risk missing the true essence of a person. In Hollywood, actors are often treated differently based on their physical appearance. Studies and anecdotes have revealed disparities in casting and career opportunities based on factors such as age, race, and body type. Actresses like Viola Davis have spoken out about the difficulties they encountered in Hollywood due to industry standards of beauty, which often favour Eurocentric features. [5]

The idea that physical anomalies are associated with villainy is a common trope that reinforces the notion that beauty is linked to goodness. This archetype is exemplified by characters like Shakespeare's Richard III, who is depicted with a hunched back and withered arm, using his physical deformities as visual cues of his moral depravity. In a similar vein, well-known villains such as Darth Vader from "Star Wars" and the Joker from "Batman" are often portrayed with scars or disfigured faces, symbolizing their descent into darkness. These examples illustrate how literature and media have perpetuated the belief that outward imperfections are indicative of inner malevolence, promoting harmful stereotypes and contributing to the equation of beauty with goodness.

At the heart of the ‘beauty is good’ phenomenon lies our cognitive biases and societal conditioning. As individuals, it's important for us to acknowledge our inherent biases and see beyond superficial differences and develop a deeper appreciation for the diverse range of human experiences. By recognizing the inherent value of every individual, regardless of their outward appearance, we can start to understand the complexity of beauty and adopt a more inclusive and empathetic perspective.

- Varun Kheria, Science Communicator, ARISA Foundation

References:

- Brain, Beauty, and Art - Essays Bringing Neuroaesthetics into Focus

- Stereotype Directionality and Attractiveness Stereotyping: Is Beauty Good or is Ugly Bad?

- Facial attractiveness: evolutionary based research

- Halo Effect In Psychology

- How to Get Away with Subverting Racial Aesthetics: The Politics of Viola Davis’s Hair and Skin