Beyond The Ticking Clock

At the end of every 24-hour cycle - it’s the beginning of a new day, after every 30 days or so - a new month, and after every 365 days - a new year. Humanity has broken down time into endings and beginnings ever since we have existed. One such ending/beginning just passed by as we welcomed the year 2024! Without getting into the semantics of what qualifies as ‘a new year,’ I want to pull focus towards a much more daunting question- did time really go by? And is your brain aware of it?

A quote from some obscure movie comes to mind, “Clocks don’t measure time, they measure themselves!” We intuitively know that time has never conformed strictly to a linear representation. Isolated incidents may have a set sequence, but how the human mind senses it, perceives it, and then stores it in memory cannot be called linear (Clewett et al., 2019). How we perceive time and how it is represented in our brain has always found its expression through art; be it a narrative medium or a more abstract depiction. Timekeepers, such as watches, clocks, calendars, etc., straighten time into a linear sequence of events.

This is because time perception overlaps with long-term memory encoding. To ensure our brain remembers something for a long time, we associate the new information with pre-existing information, thereby disrupting the linearity of time when it is recollected. Have you ever had someone walk past you, and the scent of their perfume made you think of a someone who used to wear the same scent? Recalling memories from a distant past uses subjective information from our senses to act as cues for the recall, in this case, the scent of the perfume and the emotions associated with the person who used to wear it.

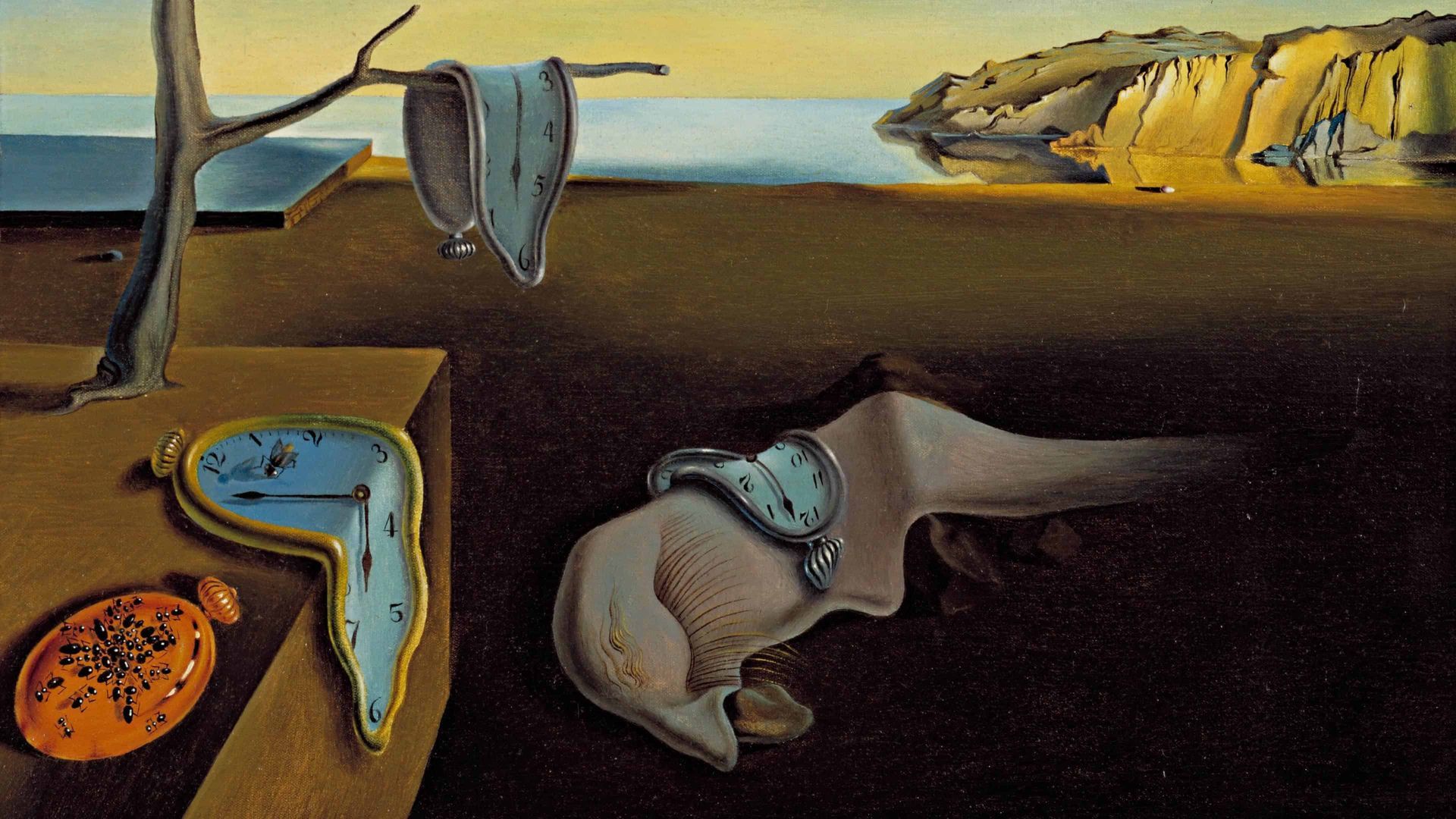

This loophole in time perception has often lent itself as a malleable tool for art, giving it a sense of incomprehensible subjectivity. Let’s take, for instance, Dali’s famous painting, ‘The Perseverance of Memory’.

This painting is also famously known as Melting Clocks and is known for its surrealist representation of the subjectivity of time - something that seems unreal or impossible but conveys its message nonetheless. Each clock depicts a different time, none of which are malleable. Seated in a desert with ambiguous lighting, the clocks are a commentary on time and the setting of the painting itself. Dali explores the subconscious representation of the distortion of time. The mind time does not abide by physical time. As much as experiential, the mind time is intricately woven into thought and the self. So many measures of time yet no one can tell what time of the day the painting is situated in.

However, the painting still seems to make sense to the human mind. We can conjure an interpretation of time even from an obscure representation in this painting.

It’s hard to wrap your mind around how time works or how we have interpreted the workings of time so far. Most interpretations are limited by its medium. For example, sitting in for a math exam always seems to be excruciatingly longer than watching Om Shanti Om - both of which are roughly around 3 hours long. Here, the task defines how we perceive time. While the math exam may elicit feelings of dread or anxiety and require the brain to take on a lot more of the cognitive load, watching a fun movie usually engages the pleasure sections of the brain. However, this does not reveal much about whether or not our brains can tell time.

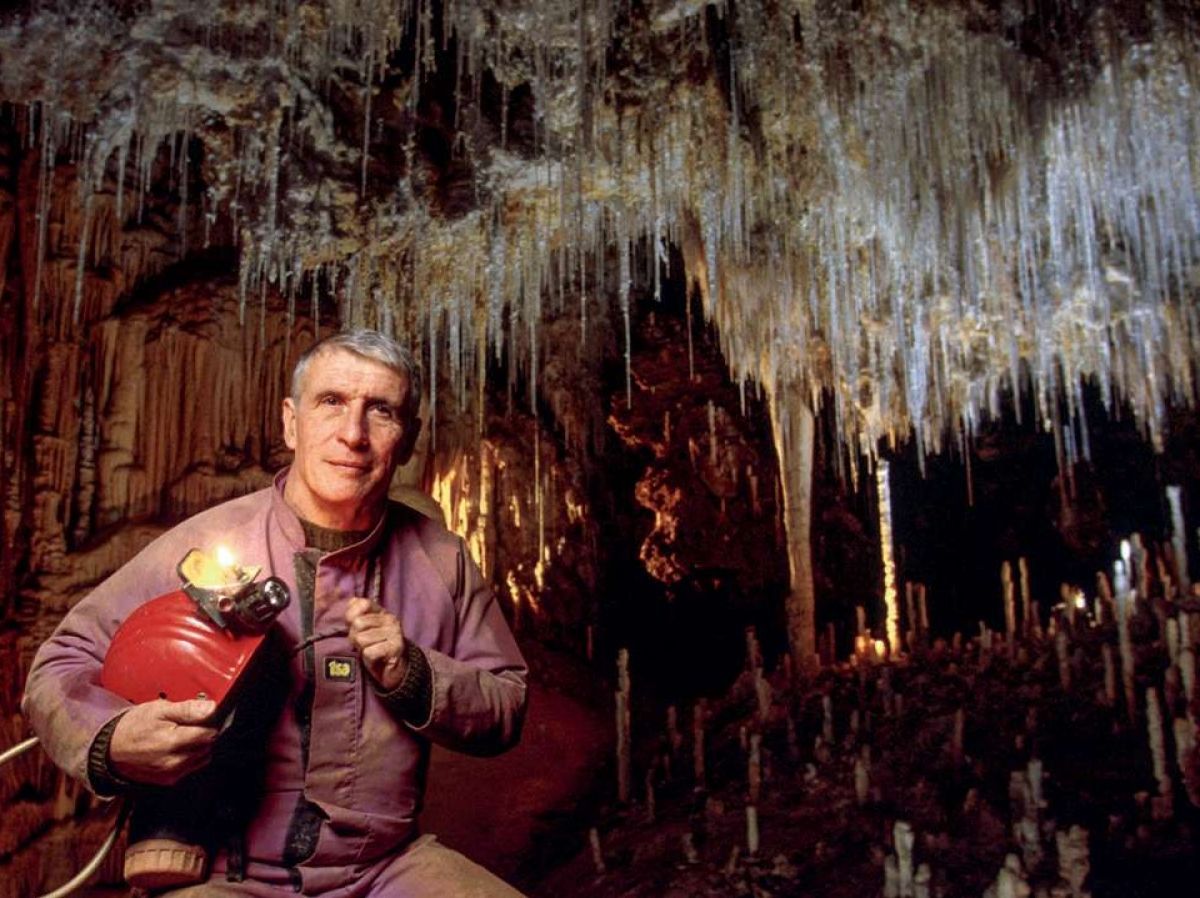

To wrap his head around this very same question, French Geologist Michel Siffre, goes underground but comes up caught in a time warp! Siffre went underground on a mission to live without environmental markers of time, such as sunlight, the sound of birds, temperature etc. He also made sure he didn’t have any timekeepers on him (watches, phones, dials) to indicate how much time had lapsed. He relied mostly on his circadian rhythm to measure the duration of his expedition. A circadian rhythm is the closest anyone has come to finding an internal clock in our brains. It is the sleep-wake cycle regulated by changes in light (sunlight) in the environment (Reddy et al., 2023). Counting one sleep-wake cycle to last for 24 hours, Siffre said he had spent 35 days underground. In reality, Siffre’s inner clock was off by 25 days!

Interestingly enough, Siffre took on two more of these expeditions- the second time in his 30s and the last time in his 60s. Each time he resurfaced, there were cognitive and physiological changes to his body, including poor vision and memory deficits.

However, his estimation of how much time had passed seemed to get much more accurate as he aged. In his 20s, Siffre felt time pass by a lot slower than it did and overestimated the time he spent underground, while in his later expeditions, Time passed by relatively faster, making his estimations closer to accuracy. This phenomenon was studied and theorised as a function of age.

To understand time as a function of age, we must first look at time as a sensory input. Although time is ubiquitous in experience, there is no specific sense organ designated for the perception of time (Wittmann and van Wassenhove, 2009). Our brain uses information from all the other senses to put together a sense of time or what chronobiologists call ‘the mind time’. This could include visual information about daylight, tactile information about temperature, as well as our internal emotional state while perceiving this information. We tend to associate categories of stimuli with each of these sensory inputs, creating a sequence of stimuli perception and interpretation.

Adrian Bejan (2019) proposes that the rate at which we process these stimuli tends to change as we age due to the physical wear and tear of the brain. We also develop more complex neural networks, like how a small town transforms into a megacity over a few decades and develops traffic problems that didn’t exist earlier. Yes, I am looking at you Bangalore. The overlap increases the time taken for a neural signal to travel across these pathways. Therefore, we are accommodating for ‘mind time’ to catch up with physical time, which in retrospect, feels like time has been moving faster. This also explains why summer vacations in primary school felt endless, but even a four-day weekend seemed to go by in the blink of an eye.

Time did not slow down for us, nor did we catch up with it. Time simply stayed the same while our brains began perceiving it differently. Summers didn’t get shorter (no thanks to global warming) but simply stopped being vacations. Our understanding of the world grows and prunes with every new information. Given its physical manifestation and subsequent emotional reactions, some information tends to bring new hope to lives. Hope that we love to label as beginnings. Conversely, some negativity needs to be put to rest and given conclusions. Conclusions we call endings.

The calendar does not accommodate each of these beginnings or endings. But it does what Time loves to do - repeat itself. So we celebrate repetitions of physical time; birthdays, anniversaries, and New Year's. The mind time, however, continues to persevere through multiple endings and beginnings regardless of its duration measurements. I believe that, ultimately, our brain dictates how we tell time and takes delicate measures to give us hopeful beginnings even in the most dreadful endings.

- Tanvi Raghuram, Senior Research Intern, ARISA Foundation

References:

- Bejan, A. (2019). Why the Days Seem Shorter as We Get Older. European Review, 27(2), 187-194. doi:10.1017/S1062798718000741

- Clewett D, DuBrow S, Davachi L. Transcending time in the brain: How event memories are constructed from experience. Hippocampus. 2019; 29: 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.23074

- Reddy S, Reddy V, Sharma S. Physiology, Circadian Rhythm. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519507/

- Wittmann, M., & van Wassenhove, V. (2009). The experience of time: neural mechanisms and the interplay of emotion, cognition and embodiment. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1525), 1809–1813.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0025